The old woman ladled broth and noodles from the clay cook pot into a wide wooden bowl. “Whatever your problems, they can wait until your stomach is happy with hot soup.”

Icho wiped a hand across his eyes. “No! You don’t understand! My family – ”

“Yes, yes, your family.” A spoon and a splash of shoyu, and she pushed the bowl towards him across the low table. “Problems can wait until after soup.”

“I can’t eat! Bandits attacked my village! They killed my father, and, and – ” Icho looked around the hut, eyes wide. He saw fire, bloody blades, his father falling. He’d run, run so fast he thought he might die like a coward and not his honorable father’s son. He’d eventually found the old woman when he really wanted a soldier, an army, anyone else. “Please, you must help me. They’ll kill everyone

if I don’t do something.”

The old woman patted his cheek. She was fat like a toad, with a wide mouth, and bulging eyes beneath wiry brows. She wore a simple green kimono and thick tabi. “Soup first, then talk.”

Desperate, Icho grabbed the spoon and took a sip of broth. The sweet warmth of ginger filled his head. Another. He’d had nothing to eat since his onigiri at midday. Tasty bits of daikon and egg hid in the nest of noodles. He slurped the bite of chilies and onion, the salty tang of fish sauce. Before he knew it he‘d finished his second bowl, and the autumn night had wound tight and dark around the tiny hut.

The old woman set the bowl and spoon in the wash bucket by the cook fire. “There. You have had your soup, and your stomach is happy.” She grinned with crooked, yellow teeth.

“I guess.” Icho rubbed his eyes. “Can you help me now, please? I need to reach the garrison in Nagasaki before. . .” He stifled a yawn.

“Nonsense, you can’t travel at night.” The old woman led him to a tatami mat he had not noticed against the far wall. “Rest here tonight, and tomorrow you can go for help.”

The mat pulled Icho to his knees, then his head to the barley husk pillow. “But my family. . .”

The old woman tucked the kakebuton around his shoulders. “You are a good son. Sleep now, worry about your family later.”

Icho opened his mouth to protest, and was asleep before the first word came out.

The old woman whispered in his ear, “You must go now, Icho.”

He sat up, squinting in the candlelight. “How did you – ?”

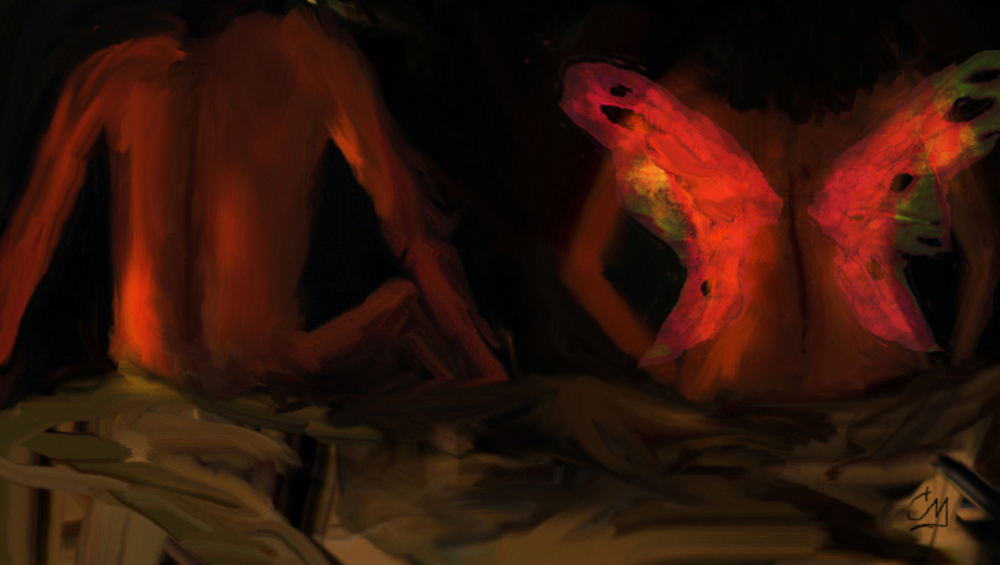

Four men in dirty padded armor sat at the low table, battered helmets beside them. The old woman moved around the table, ladling hot soup into their bowls. Icho recognized the long knives tucked in their belts, and fear splashed like winter water down his spine. Brusque chatter, and the whinnying of horses came from outside.

The old woman set the pot back on the fire and wiped her hands on her kimono. “Awake finally, hmmm?” She waddled to the tatami mat and took Icho by the shoulder. “Up and off with you, then.”

Icho clambered to his feet. He screamed a bare whisper: “That’s them!”

The old woman looked over her shoulder. “These men? Bandits? Certainly not.”

Icho clutched her kimono. The threadbare cloth was bitter with woodsmoke. “No, you don’t understand. They’re the ones who attacked my village.”

The men watched him with sharp dark eyes, dog eyes. One sneered at him, made to stand.

“Don’t mind the boy,” the old woman said with a laugh. “Eat, eat. Make your stomachs happy with hot soup before it gets cold.”

The man hesitated, then settled back with the others. He lifted his bowl and gulped the broth. His eyes widened, he smacked his lips, and nodded to the others. After a moment, they lifted their bowls to join him.

The old woman walked Icho towards the door. “Head back home. Bring me noodles for my soup the next time you come this way.”

“They’ll kill us. We have to – ”

The men standing with the horses looked up from their dice as she pushed Icho outside.

“Of course not. Get on home now.” She motioned the men inside, her eyes sickly yellow in the dim light. “Come in. I have soup to warm your bellies.”

The dark woods reeked of smoke and hot metal. Blood and death grabbed Icho by the heart and he ran, the way he ran when the bandits came for his family. Left the old woman standing in the doorway, her terrified screams so much like his mother’s! Icho raced his shame into the night until fear tore the breath from his chest and he tumbled into darkness.

The next morning, Icho followed his shame along the path of broken branches to the hut. His coward’s heart would have rather kept running, but honor demanded he return. If he couldn’t apologize for his cowardice, he could still bury the old woman’s body then give himself to the sea in shame.

He stopped at the edge of a small clearing littered with slick, white bones and bits of cloth. Shreds of padded armor hung from dead black branches overhead. In the center of the clearing, leather reins knotted around a pile of human and horse skulls at the base of a small stone altar. A fine breath of smoke hung in the air, then drifted away on the wind.

Icho walked to the altar. He pressed his palms together and bowed low to the stone soup pot perched on top. A master’s hands had given it life – a wide toad mouth with crooked teeth, and bulging eyes beneath lightning brows. “I thank you. My village thanks you. My father thanks you.”

On the other side of the clearing stretched a wider path made by horses. Icho started home. Noodles. He would not forget.