We fell for each other.

Hard.

Like stars, it seemed.

Had I thought about falling stars then, how they’re just bits of space dust burning up as they hit the atmosphere, it likely would have taken some of the Zing! out of my romantic illusions.

But I didn’t think about it.

It was like we’d been made for each other, something I did let myself think even though I knew the cliché was only half true. I was as I’d always been. She, though, she’d been made for me.

By me.

It was a simple enough process. I’d designed every bit of her, filling in all the blanks and boxes on the Realationship™ site. And when I say design I don’t just mean the parts you might think. But everything. Down to the shape of her toes, the curve of her eyebrows.

I remember sitting at the keyboard, my fingers caressing the track pad, working my way through eye color and skin tone. Each drop down menu needed a carefully considered click, like a little nudge, a little push. Each choice opened a window to more, with all of them weighed against the ones that had come before.

And there’d been myself to consider as well–measuring my lips to match against hers, moving my hands in just the right way to see how they’d feel on the small of her back, following the prompts to upload my image so I could see how my brown eyes would reflect her blue. Finished, I’d just needed to click on all the agreements, debit my account, and wait for delivery.

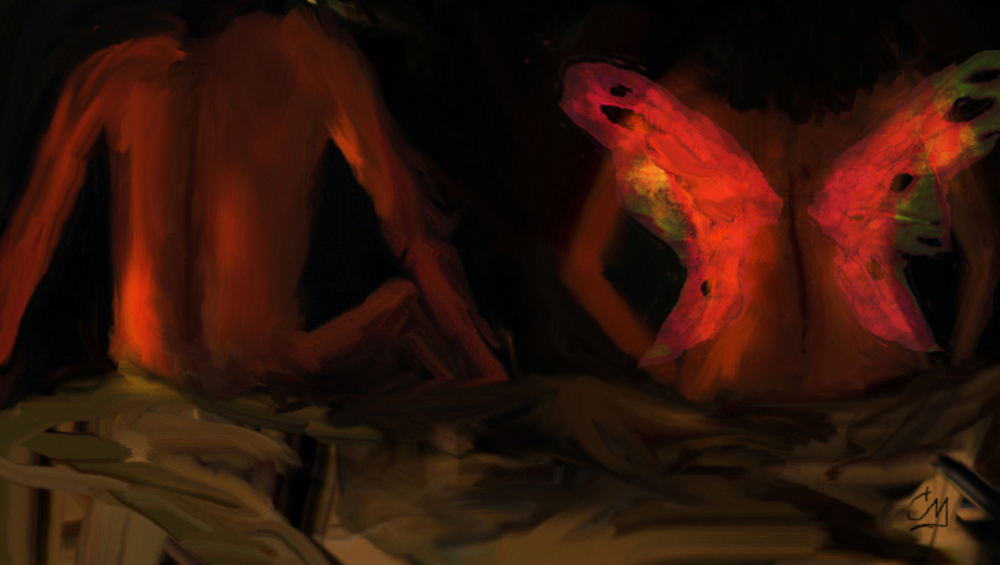

The night I lost her, we lay in the back yard, a blanket between us and the ground. She rested her head on my arm, her blond hair threatening to make me sneeze as it tickled my nose. Our sweat had already begun to dry from the summer breeze, and if I moved my hand just a little I could trace the swell of her breast. It would have been perfect if we had seen a falling star then, but the cloudless sky yielded nothing but familiar constellations.

“What time is it?” she asked.

I’d designed her to disregard the tech she ran on. Occasionally, I’d hear a servo spin somewhere in her body, but if she ever heard the same, she ignored it. And so, though her operating system included a perfectly accurate internal clock, it was instinctive of her to ask me the time or to check the delicate watch I’d given her on our one-month anniversary.

She wasn’t wearing it now. Or anything else.

“Almost ten,” I said after raising my wrist and blocking out part of the sky for a moment.

She seemed to take a second to process the information, then sat up, leaving my right arm and whole right side suddenly cool as the night air touched the skin she’d just been pressed against. I smiled at the sight of her naked back.

“I’m leaving,” she said.

My smile faded.

“Leaving?” I asked, nonplussed. My turn to process.

“You,” she added.

Then she was up. Off the blanket and picking through the clothes scattered on the lawn.

“What do you mean?”

“What I said. I’m leaving you.”

I was one of three foremen who ran the Purifier for the General Secretary before and during the upheaval. Those were dark days for all of us, and anyone who can sit in a rocking chair by the fire, warming his fingers and talking about those times, is lucky. Lucky to be alive, lucky to have his fingers still, lucky to have his tongue. But not everything about those times was evil. Like all times, in all places, I suppose, some bits of light make life worth living, grim as things might get.

I was one of three foremen who ran the Purifier for the General Secretary before and during the upheaval. Those were dark days for all of us, and anyone who can sit in a rocking chair by the fire, warming his fingers and talking about those times, is lucky. Lucky to be alive, lucky to have his fingers still, lucky to have his tongue. But not everything about those times was evil. Like all times, in all places, I suppose, some bits of light make life worth living, grim as things might get.