I only remember bits and pieces of my first night at Whitestone Wall, looking over into Lios Iridion. The crinkling fires. Tussocks of grass and hard earth underfoot. Hot dogs from a briny tin: plump and pale marshmallows on sticks. My father lifted me up to look over, and I braced myself by putting my feet against the blanched stones of the ancient wall.

On the other side it wasn’t night.

On the other side it’s never night.

Other men from the town had brought their sons, too. They sat in communal circles on foldout chairs around their own campfires, or stood at the wall themselves, holding up their boys: each and every one of them hopeful that his son was special somehow; each and every one of them hopeful that, tonight, there might be a sign.

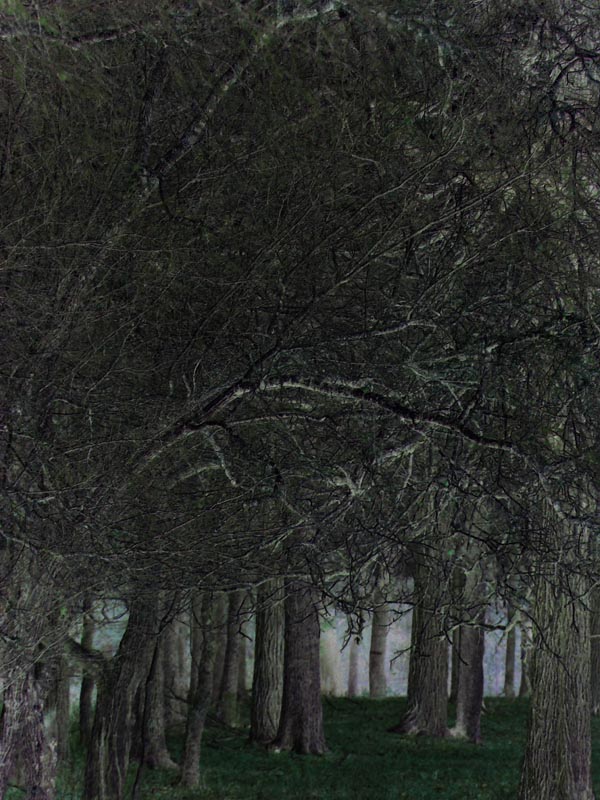

On our side the night was a glassy black, the tree-lined ridge between us and town obscuring the stars. The shafts of many-coloured light that make up Lios Iridion took up the whole of the other horizon, tinting all faces with garish hues.

My father put his lips to my ear:

“I think I see something in there!” He whispered, his moustache scratching against my earlobe. Then, after glancing along the lines of arrayed men and boys either side of us:

“Shhhh… ”

“A Way Through The Trees” by Christopher Woods |

I don’t know when my father’s troubles with drink began. Maybe they were always there. I know it was around about the same time he first took me to look over Whitestone Wall that his troubles spilled over the glass and into the house, though ‘cause the heating bill didn’t get paid that winter. In the mornings, before he roused and fed the stove with pages torn from my mother’s old pattern books, our breath would be on the air. He had me sleep by the stove that season. I remember that. And I remember asking him how he’d keep warm:

“I’ll be chasing beaver all night long,” he answered, with a dusty laugh. He still had some of his handsome left back then, but when he looked to see if I got the joke he saw only the pain I was feeling to see Ma’s things being destroyed.

“She wouldn’t’ve wanted us to go cold,” he muttered and reached out to me with his powdery, mason’s fingers. I pulled my blankets tight around me and his hand went back, to his mouth, covering up whatever was going to coil out of that as his eyes hardened, putting a rime of white on his black moustache, his stubble, his greying skin.

The curtains were open over the sink. Through the greasy quarters of the window one of his abandoned statues loomed, an abstract mass of dull metal and wire and flags of dishcloth. He called such things his ‘true work’, as though saying so negated the fact that by day he made veneer tiles at the quarry, tiles that the big trains took away to the city to never be seen again. Occasionally he’d do the odd bit of repair work on the dry-stone walls of outlying farms, repairing the places weather or livestock had undermined. His skill was acknowledged enough that it was he who maintained the cairn of stones around the Mancer’s Block by Whitestone Wall, too. I think he even received a stipend from the aldermen for that duty. He never told me much about his work – no techniques, and no trade secrets, either – so I can’t say for sure. He didn’t want stone to be it for me, that’s all I know. He wanted my destiny to waltz up to me from the other side of Whitestone Wall.

But what father in town didn’t want that for his lad?

What father in any town so close to the wall?

A boy with the gift to see remarkable things in the lights might join the rhapsodomancers of the cities, after all.

That first night he lowered me back to the land, out of the warm fug of his boozy breath and silly talk, and back to the crisp and fresh cold that seemed to me to be rising from the rough ground. He gestured with one hand towards our fire and our blankets and bedrolls, and with the other gave me an urgent shove.

“Go to sleep now,” he said. “I’ll be just here.”

He took his flask from the deep front pocket of his jacket and turned back to look into the glowing colours of Lios Iridion.

Fionn would have been about 16: a black-haired boy, rangy and with a bony face. I think he lived just with his mother, somewhere near to our house, for I’d seen the two of them walk past our little place from time to time: sometimes just the one of them, sometimes just the other. Always stopping to stare. People often did. My father’s twisted sculptures, a tangled forest of pale stone that defied explanation, fascinated and appalled people equally.

“You’ve got to tell your own tale,” he’d muttered to me, once, when I asked him what he thought he was making. He didn’t look around at me at first, but then, sensing I still lingered, he lifted his eyes from their concentration upon what his hands were doing with chisel and mallet:

“You don’t get it, do you?” he said.

“I do. Sort of,” I said, squinting up at the sculpture. He’d carved what looked like a tree with all of its branches snapped off. A denuded thing, with a serpent twining around its trunk. The smell of rain was in the air, a change in the weather.

Later – maybe it was the evening of that same day (though that may be a trick of convenient memory) – I went at twilight to Whitestone Wall. I associate the two incidents because I know I was thinking about what my father had said to me about his true work when I went there that dusk, as though his words were a spur. He was gone for the night, as usual, out somewhere wetting his whistle.

I didn’t go to the spot he’d taken me to when I was just a kid, the place everybody seemed to think was where visions were most likely to come. I walked north through the woods, in the direction the trains went when they were going up to the cities. There was a spot by a stream there where Whitestone Wall wended a little to the west.

When I got there I saw Fionn was there, too. He turned, hearing me coming out of the trees and through the bobbing bracken, and looked at me for a moment.

“You’re his son,” he said. “The mason’s, I mean.”

“Yes,” I said.

I went past him to the wall and propped myself up on the irregular top stones, the upright ones my father called the ‘teeth-bits’. The rain began to fall then, a drizzle. It felt to me that I’d been holding my breath. Behind me Fionn was quiet, still. Eventually he came and stood alongside me and I breathed again. Fionn leant, cross-armed on the stones, too. Between Whitestone Wall and Lios Iridion, on the hundred yards or so of sedge grass that is that realm’s own natural border, there was no rain, only the rainbow. The eternal rainbow’s end.

“It’s been fifty years since anyone from town saw anything over there,” Fionn said. “Yet still we come and look, don’t we?”

“What did they see?” I asked him.

“There’s nothing over there to see,” he said and his voice was bitter.

“The Rainbow People are long gone. There’s nothing beyond the lights.”

“Why do you come here if you think that?” I wondered.

His smile was a twist. “There isn’t anywhere else I can be just now,” he said.

I don’t know how much later it was that I was woken one morning by the telephone. Spring had come by then, but the mornings were still cold. I stirred in my hard bed. That year I’d fallen into the strange habit of flinging my arms above my head when I slept and my legs out from under the covers so that I woke up with numb limbs. The telephone kept ringing. I shuddered up and stumbled through the house to the hallway and picked it up. It was my father:

“Go to Whitestone Wall,” he said, without preamble. “Fionn has seen something.”

“What?”

But he’d already hung up. I wondered where he was. Flopped out with some drinking buddy, I supposed. Then what he’d said reached my brain: something had been seen. I rubbed my sore, bare arms and went hurriedly to dress.

Out on the streets people were rushing in the direction of the wall. I heard many saying that a rhapsodomancer was coming, that the Mancer’s Block was glowing for the first time in decades.

I got there just a little ahead of everyone else – I’d run, unashamed, where they had mostly taken on a brisk clip in order to save their dignity – and so I was one of the few who saw the rhapsodomancer appear. There was still a thrum in the air when I looked behind me, my eyes wide and wanting to share the wonderment of what had just happened with someone, anyone, and I saw my father staggering along the shale road that ran under the ridge, his hair in crazy corkscrews and his shirt-tail flapping out from under his coat. There was a woman moving ahead of him with more urgency. Her hair was unbound and she wore just a grey shawl over her nightdress: Fionn’s mother.

My father glimpsed me at the front of the crowd and gave a slapdash wave, a signal I should look around and pay attention.

The rhapsodomancer wore white robes. His hair was white too, but his face was youthful.

Fionn stepped forward from the crowd.

“You saw something?”

Fionn inclined his head. “Yes.”

“What?”

The boy smiled that twisting smile I’d seen, his eyes sidling to the crowd. “Should I say aloud? In front of these?”

The rhapsodomancer’s own lips twitched with sour amusement. “You can say a little, I think.”

“It was beautiful,” Fionn said, his lips twisting.

The rhapsodomancer nodded knowingly. He held out his left hand. “Come with me, then,” he said. He pulled back his robe. On the rope belt wound around the toga underneath there hung a sickle.

“Fionn!” The boy’s mother gave a desperate cry as her son reached out and took the rhapsodomancer’s hand in his.

They were gone in a blink.

Behind the place where they’d been Lios Iridion came back into focus for me. I saw something moving between the bright shafts. Just then my father’s hand fell on my shoulder and I jumped. Fionn’s mother gave an anguished cry, the crowd parting around her. She fell to her knees on the grass. My father’s hand tightened sharply.

“How did you know Fionn’s name?” I asked him.

Still catching his breath from his haste to be here, he snatched his eyes from the grieving mother to me. “What?”

“Never mind,” I muttered. His eyes went back to her, Fionn’s wailing mother, and his grip on me tightened again, a pain, a buckling weight on my shoulder.

I looked back over Whitestone Wall.

It wasn’t beautiful, what was moving in the light over there.

It looked at me, and then moved on.

We never saw Fionn again.

I started dating Siofra out of spite: I suspected my father was diddling her mother, the art critic on the town’s newspaper, and wanted to complicate things for him. I was 19 then, an apprentice in the mosaic workshops, Siofra in her last year of school. I had money. Money is a good thing to have when you’re dating a girl of 17; only women with more experience of life and disappointment can forgive a man its scarcity.

Things had changed in town over the years. The soul of the place, I mean. My generation was filling out, beginning to pass out of the age when seeing things over Whitestone Wall was possible for us. Now we were having to face up to the fact that, whatever we were, that’s what we were always going to be. I made tiny tiles, mixed grout and helped the old mosaicists with any heavy lifting. Nights I’d sit on the veranda at Siofra’s place, drinking, smoking and nuzzling. Around about that time my father had been making noises about putting on an exhibition of his best sculptures. Siofra made excuses for her mother’s absences, saying there was a big project she was working on, something about the cultural history of the town, the impact of Whitestone Wall on local art. I forget now what her father did, or why he was away so much her mother sought comfort in a man like my father.

Does it matter?

It didn’t matter then.

I taught Siofra how to roll cigarettes. How to avoid hangovers. How to function in school the next day if that cure didn’t take.

It was a hot summer, headache weather, the time of year when fathers took their sons to Whitestone Wall most often, at cloudless twilights fragmented by glimpses of lightning far-off to the south and beyond the plains. Siofra would lift her hair off her neck lazily on such nights, her arms going up and pulling her body taut, standing before me. A reach down and then a new bottle of beer from the ice-box – pressed to her forehead, then to her lips.

“If you don’t wanna see what’s shaking at the wall we could go to the woods. Some of the guys are having a camp-out.”

“Alright.”

I knew she liked to show me off and I was in an indulgent mood.

We went into town and I bought more beer. The sky was an iron griddle above us, the night a refuge for twitching things; insects and night-birds. We walked up the sloping meadows. The path into the trees was soused with the colours of distant Iridion. Ahead of us music and voices commingled somewhere in the gloom. The sound of a beer can being opened, the flare of a match. Some skinny kid was sat on a log, playing a guitar. Riona, the girl I’d dated the summer before, was there, in a long skirt and a sleeveless top. The fashion for wearing black was on us once more. In the dark Riona’s limbs were long and white, unattached to a visible body: dancing, drunk.

Siofra took my hand. We sat and we drank too; and we talked nonsense and everybody was loose and languid in the way a hot night can make you. And then, at some point, I decided I needed to relieve myself, but that I wasn’t going to do it too close to where we were. I disentangled myself from Siofra’s sprawling legs, lifting her hand from my belly, and I wandered into the trees a fair way.

I could hear a stream now I was away from the others, a plosive burbling over rocks. When I came to it I decided that that was as good a place as any for me to do my business. As I stood there the night resolved itself and I saw how close I was to Whitestone Wall, to that place where it bends just so, where Fionn and I had once stood, waiting it out as our parents rutted.

As I peed I looked at the wall, thinking of what my father had said about the craftsmanship that had gone into making it in the first place, about how weird it was that no moss grew on those stones; how strange that no creature dared make a home in any of its nooks and crannies. How the rhapsodomancers had bound the Rainbow Folk within its boundary.

But these were mysteries I was ready to leave to others.

As I gave myself a little shake and began to zip up my fly a voice called out:

“Hallo!”

On the other side of Whitestone Wall there stood a gentleman.

I really don’t know how else to put it.

Gentleman.

It was not a word I had had recourse to use ever before. He wore a fine violet coat with trimmings of red lace. His hair was a purplish hue. Yellow breeches and long blue socks led down to shoes with orange uppers. In his left hand he was dangling a glistening, indigo handkerchief. Behind him the shafts of Lios Iridion were still there, but they were lessened somehow. Through them I could see a city now, a place of high columns and mighty arches.

“Hello?” I responded, tentatively.

The gentleman, whose face was quite florid, smiled, showing two rows of needle-sharp teeth. His eyes were a merry colour I have no name for.

“Yes, that’s right,” he said. “You. I am talking to you. I’ve seen you before, I think.”

I put my hands in my pockets and stepped over the stream.

“I don’t think so, sir,” I said. “I’d surely remember that.”

The gentleman laughed and came all the way up to Whitestone Wall, beckoning me closer to chat, as neighbours might. I ambled down the undulation of the land towards him.

“What a night!” He exclaimed. “Quite enchanting, don’t you agree?”

I nodded and his smile widened.

I didn’t like those teeth.

Not at all.

“I thought to myself that this was just the right kind of night to go for a stroll,” he went on, “the kind of night when one might encounter something or someone interesting. And here you are! What a good boy! It’s enough to make me think I should invite you over. I think you’d like Lios Iridion.” He gestured to the city behind him with a flap of his handkerchief. “All sorts of wonders await a delightful lad like you in that city!”

I glanced over his shoulder. Now I was at the wall I could see the place better. There were things gyring in the air above it and I began to entertain the notion that those buildings were not marble at all, but bone: the bones of great creatures, beached on shores of bright dreams, that a being such as this gentleman thought it no big deal to fillet.

“Shall I summon my carriage?” He asked, airily.

“No,” I said. “That’s alright.”

His fey eyes narrowed. “No?” He breathed softly. His angular nostrils flared. “No?”

I shrugged. Behind the gentleman the lights of Lios Iridion brightened, obscuring the city once more. The gentleman’s mouth widened yet further, splitting his cheekbones. The colour of his eyes was like bile now. Fish eyes in a fishy face. I walked back into the woods before I had to see anymore.

The air thrummed as I neared the stream. A man appeared on the other side: the rhapsodomancer who had come for Fionn, returned alone and without fanfare.

“You saw something.”

“Nothing I’d tell you about.”

The rhapsodomancer laughed. “Those who lie to my kind always meet a sharp end. That was a lesson worth learning, I think.” He pulled back his robe. On the rope belt wound around the white toga underneath there hung a feather, striated with blacks and greys and whites. He plucked it and held it out to me, over the tumbling water but I shook my head. He shrugged. The air tensed and then he was gone. I stepped over the stream and began to work my way back to the others through the gloom. A few steps along the way I saw long, white limbs floating in the dark: Riona.

“I got lost,” she lied.

I put one hand on the back of her head, the other to her hip where her black top pulled away from that long skirt and I pulled her close to kiss her. She smelled like her dancing: sweaty and heady.

“What about Siofra?” She asked, a minute later.

“She doesn’t make me happy,” I said.

One lie deserves another.

Not getting his exhibition that year lessened my father. Not getting anything we want lessens all of us, of course. Setting aside something, though… Some call it cowardice and some call it courage. But we each of us have to tell our own tale – most often blindly and with no idea of how it ends.

Tonight Siofra, who went on to open a gallery in town, called me and asked me to put a show on there later this year. A retrospective of my abstract work, she said. A little later, Riona came and said our boy had asked to be taken to Whitestone Wall soon. He’s five. It’s about the right time, whether I like it or not: people will think it’s funny if I don’t.

I came in here after they both went to sleep.

Had myself a little drink.

Something my father said to me came back to me just now. It was right before the end, I think, on one of those days when he’d just turn up unannounced at my workshop. He stood, swaying, looking at the things I’d made and had started daring to call ‘art’, his face flaccid, his hair hoary with chalk: already a ghost in the making. I suppose we all are. I looked at him looking. He put a hand to his mouth and then took it away, like he was wiping his lips dry.

“Art,” he said: “It’s dropping a stone into water and trying to catch something of the ripples before they’re gone.”

“It’s looking for the gold at the end of a rainbow,” I said, idly, as I reached for my wallet.

“Don’t give me anything if you think I’ll only spend it on booze,” my father had said then, lifting his eyes from my trays and my tiles.

It didn’t make any difference to me what he did with the money I gave him, but I didn’t say so. I just handed him a few coins. There was something white in his hair – a bit of tissue I thought, or a clump of dust. I plucked at it with my quick fingers and studied it for a moment. A fluffy trace from a black and white feather. Where had he picked that up?

I wondered then if I should have taken the feather I was offered all those years ago; accepted it and pared it into a quill and written my life’s tale with that.

I showed my father what I’d taken from him, but he was only smiling – wearily, beautifully – and looking again at the abstract piece I was working on.

“I think I see something in there,” he said.

I shook the feathery tuft from my fingers.

“Shhh… ” I said.

S.J.Hirons has previously been published in Clockwork Phoenix 3 (Norilana Books), Subtle Edens: An Anthology of Slipstream Fiction (Elastic Press), Daily Science Fiction, SFX magazine’s Pulp Idol 2006 anthology, 52 Stitches (Strange Publications), Title Goes Here magazine (Issue #1, Fall 2009)., A Fly In Amber, Farrago’s Wainscot, Pantechnicon Online and The Absent Willow Review and has upcoming stories in The Red Penny Papers as well as at faepublishing.com.

The Colored Lens is a quarterly publication featuring short stories and serialized novellas in genres ranging from fantasy, to science fiction, to slipstream or magical realism. By considering what could be, we gain a better understanding of what is. Through our publication, we hope to help readers see the world just a bit differently than before.

If you’ve enjoyed this excerpt from the Autumn 2011 issue of The Colored Lens, you can read the publication in its entirety by downloading it for only $0.99 in e-book format for Kindle or Nook, or you can read a free sample of this issue in your Google Chrome or Safari web browser by clicking here.