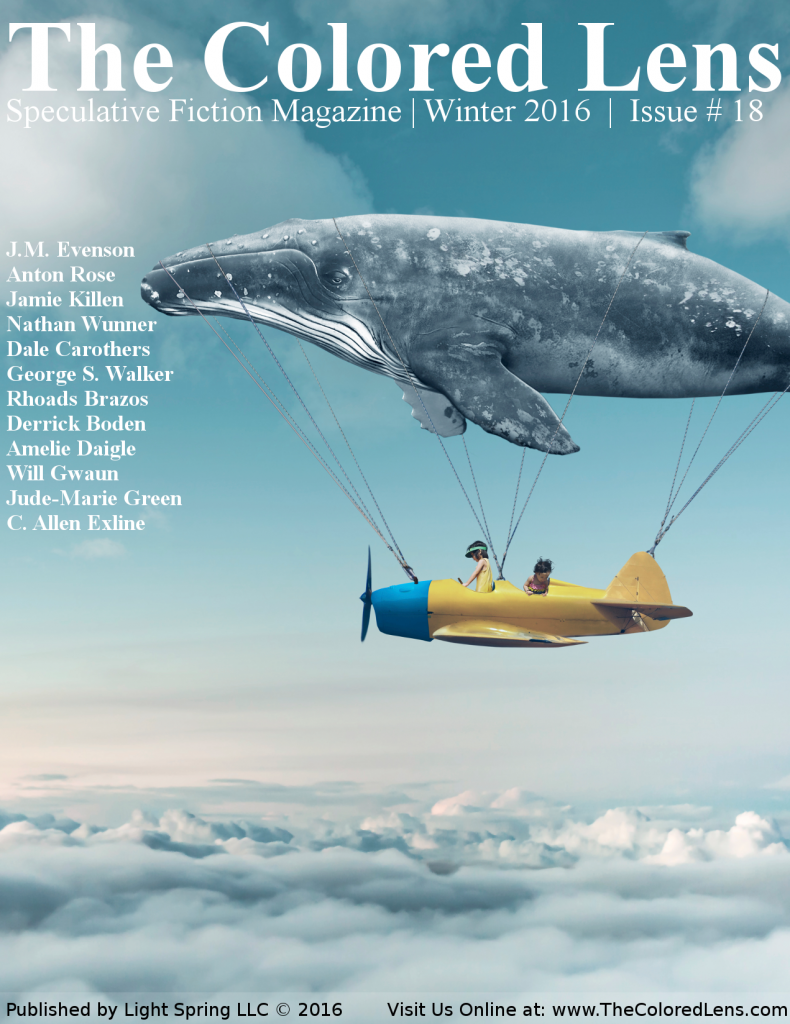

The Colored Lens

Henry Fields, Associate Editor

Table of Contents

- I Will Bring You Home by George S. Walker

- Me and My Heart by Anton Rose

- These Old Hands by Jamie Killen

- We Are Stardust by J. M. Evenson

- Lighting Fire To Ashes by Nathan Wunner

- A Life Lived Above by Dale Carothers

- Marching into Blue Climes by Rhoads Brazos

- A Memory, Perfected by Derrick Boden

- Others by Amelie Daigle

- Pixel Heart by Will Gwaun

- Miracles Wrought Before Your Eyes by Jude-Marie Green

- Darkly with the Shadows by C. Allen Exline

I Will Bring You Home

By George S. Walker

A thud of rock woke Sykeet, followed by a rattling of dislodged crystals against the woven walls of her hanging hut. There were no fire pots in her lower reach of the rookery. No light from the moons, either: a storm beat against the suspended village. Her wings twitched in the dark.

There was cursing, then a shriek of panic, “The fledglings!”

Sykeet darted from her hut like a harpoon, flying blind toward the crèche net. Her long wings beat the air, lifting her upward. Sleet hissed against rock, giving her only a minimal sense of location in the dark. More rocks thudded above. She heard the twangs of over-stretched ropes snapping.

She called shrilly to her daughter, “Kyree!”

There were voices in the dark: other mothers and the faint cries of fledglings. Then from above, a wild flapping of fabric and netting. She couldn’t see a thing.

The falling canopy hit her, a glancing blow that knocked loose feathers and sent her tumbling in the dark. She heard waves crashing against the rocky base of the spire below.

Sykeet caught air in her wings, regaining control. Still blind. The plummeting crèche net had fallen below her. She pulled her wings against her body and dove into what she hoped was open air.

“Kyree!” she called again.

The panicked brood, trapped in the net, screeched as they fell toward the sea.

Sykeet followed their cries. The net hadn’t snagged on the crystal-crusted spire. If she could catch it with the talons of her feet or wings, she might slow its fall.

But a gust from the storm blew her sideways, away from the screams. She beat air frantically, trying to get back.

There was a splash as net and brood plunged into the sea.

“Kyree!”

Cold sleet crusted her feathers, numbing muscles. Spray from the waves blew against her as she fought to stay above them, circling blindly and calling, trying to find her daughter.

Unable to see, she slammed into the spire. Pain shot through her. Dazed and disoriented, she grabbed hold, talons clutching crystals. Fragments cracked loose from the rock. She slipped closer to the waves. Sea spray filled her open beak as she turned toward the water. She choked and coughed.

Sykeet could only cling there, shivering from pain and cold, too numb to take flight. She listened for fledglings, hearing only the roar of wind. Waves pounded the rocky base below her. Her eyes stung from sleet and spray. When she tried to climb lower, more crystals broke off, nearly dropping her into the cold sea.

She folded her wings close against her to conserve heat, and pressed her head against the rock. The world had gone dark, taking the thing she cherished.

She shivered through the night, praying for some sign that her daughter had survived. She saw nothing, heard nothing.

But in the dark hours of early morning, she suddenly dreamt she was elsewhere. Sleet and spray still beat against her, but instead of the rocky spire, she felt she was pressed against something smooth. A net held her down.

Then the dream was gone, as quickly as it had come.

Other mothers from the rookery pried Sykeet’s talons from the rock wall in the morning. The storm had moved on, and she saw blue sky, red sun, and white clouds as they flew her in a net to the aerie above. Their voices sang in a melody of sad calls. Sykeet remembered singing to Kyree in the crèche net. Nothing could fill that void.

Wooden perches stuck out like a thorny crown around the spire’s peak, offered up toward the giant red sun. Sykeet’s stiffness began to thaw in the sunlight as she gripped a perch facing east. Despondent, she didn’t preen her green and yellow feathers, leaving them matted from the storm.

One of the mothers, Teeka, swooped onto the perch beside her. They were both silent for a time, then Teeka said, “There will be other broods.”

“Not for me,” said Sykeet. “Fate has destroyed me.”

“Some accept Fate. Some deny it.”

“What’s to deny?” Sykeet said miserably. “I heard the net hit the water.” She remembered the splash in painful clarity.

“They took it,” said Teeka.

“Who?”

Teeka cocked her head. “Didn’t you know? The Yantay.”

The Yantay rarely ventured near the spire. “How do you know?”

“They threw the rocks that ripped it down.”

Sykeet remembered the thud of rocks and the rattle of crystals falling on her hut. If a pod of Yantay had taken her daughter, drowning was a mercy by comparison.

Abruptly she had a vision, a dream turned inside out: She was trapped in the crèche net. Its knotted mesh pressed into her feathers, binding wings and legs. Only her curved beak was partly free as she breathed between cords of the mesh. Cold water spattered her head, spray that leapt from the crests of waves breaking against the thing she rode. She scratched at reptilian scales with her wing talons, feeling cold flesh beneath. Her claws had no effect.

Teeka’s words pulled her back to her perch atop the spire. “The Lord of the rookery’s fledgling was in the net. He’s pledged rank and treasure for his rescue.”

“I don’t want that! I want Kyree!”

“Just as well. The Lord wouldn’t grant them to a hen.”

Sykeet stretched her wings. She wanted to believe, wanted to save her daughter. But a search would only bring more heartache.

Except… the vision of Kyree had been so real.

“Which way did the Yantay go?” she demanded.

“You might as well ask the wind.”

“I’ll ask the Lord of the rookery.”

“You can’t go to him by yourself!”

“I died last night, Teeka, down by the sea. Come with me.”

“What?”

“There’s nothing for me here but to finish dying.”

“Don’t be foolish!”

“Together we are two, Teeka.”

The Lord held court from a crystal cave chiseled into the spire. Lattices of rope and sea vines cascaded around the cave. The drakes clung to them, jostling for position in the swaying lattices. Their talons also clutched harpoons carved from reptile bones. Closer to the cave, the knights of the rookery wore spurs on their legs. Sykeet and Teeka had nothing. They were the only hens. If it weren’t for her daughter, Sykeet would never have come, and Teeka clearly wished she hadn’t. The knights were nearly twice their size, powerfully muscled, and the other drakes not much smaller. Sykeet took hold of a dangling rope of the lattice, beating her wings to keep from being hurled off as drakes above her whipped the lattice into a frenzy.

The Lord watched with hooded eyes from his perch in the cave. His feathers were pale from age, the feather barbs of his plumes brittle and sparse. But his curved beak was long and sharp.

The cacophony continued until the Lord finally shouted, “Silence!”

The turbulence of the rope lattices slowed, and Sykeet climbed higher. Teeka did not.

“Who vows to find the Prince?” called the Lord.

A chorus answered.

“Who vows to bring him home?”

The chorus was louder, sending the lattices swaying again. Sykeet hung on.

“Then follow my knights,” ordered the Lord.

The lattices jerked as the drakes took flight. Sykeet and Teeka were left behind as the drakes followed heading in all directions.

“Where?” cried Sykeet. “Doesn’t anyone know?”

The Lord glared out of his cave at the two stragglers.

“Why are you here?” he demanded.

“For the brood.”

“Why are you here?”

Teeka dropped from the lattice, fleeing.

Sykeet had nothing to lose. “Which way did the Yantay go?”

“This isn’t your hunt,” said the Lord.

“My fledgling, my hunt,” she snapped. Letting go with her talons, she plunged from the lattice.

Sykeet swooped down past where the mothers had rescued her, but Teeka had disappeared.

Ahead, high above the waves, she saw four drakes in an unbalanced V formation. She pounded air with her wings to catch up, breastbone straining with each beat.

The drakes dangled harpoons from ropes clutched in their hind talons. She had nothing. If there was a battle with the Yantay, it would be on their terms, not hers. She wished Teeka had stuck with her.

She was nearly to the trailing edge of the V when someone spotted her. A knight led the V. At the lagging edge was the flock’s rivener.

“Sykeet!” shouted the rivener. “Where are you flying?”

“I seek the Yantay,” she said, gasping for breath.

“As the bait?” The others in the V laughed.

“They took the fledglings!” she said.

“And you want the reward.”

“No. My daughter.”

“Yet you already threw your harpoon and lost it?”

Sykeet didn’t reply to the insult. They knew she had no harpoon.

“You should be home, weaving nets,” said the rivener.

At the head of the V, the knight turned his head, beak bright yellow in the sun. “Don’t get in our way.”

She struggled just to keep up outside the V. Her wing muscles burned from the effort. Was this even the right direction? The drakes surely didn’t know. Sykeet followed them only because this was the direction from where she’d spent the night clinging to the rock. She tried to remember clues from last night.

The Yantay swam in pods: one monster Alpha and a group of offspring. She’d watched them, but never gotten close. The reptiles had two heads on long necks, with a line of sharp dorsal spines sticking up. An Alpha must have led its pod to the spire during the storm, knowing the flock would seek shelter in their huts. A full-grown Yantay could hurl rocks gripped in its mouths farther than any harpoon. High enough to hit the crèche net. Enough rocks must have brought it down.

Afterwards the pod had swum away with the net. But rather than drowning the fledglings, they’d kept them alive. As she thought of Kyree in the net, her mental vision flipped upside down.

She was looking up from the sea, not down, still struggling in the net. Fledglings screamed as the jaws of a Yantay bore down on the crèche net. Bones crunched. One scream was extinguished. A rain of feathers scattered over the net. She smelled blood and felt herself huddle against another fledgling, beak down.

Sykeet desperately wanted to be there, to pull her daughter free. Was the vision real? If so, where was the pod? She seemed to see through Kyree’s eyes: gaze jumping between the weave of the net, Yantay scales, and a bloody mass of bones and feathers. The crèche net stretched along dorsal spines. And through the net she glimpsed a spire jutting from the sea: a double spire with a lace-work of crystals bridging the gap.

With a start, Sykeet emerged from the vision. She knew where that was.

She veered away from the flight the drakes were taking.

“Where’s she going?” one of them called.

“Who cares where a hen goes?”

But the rivener dropped out of the V to follow her. “Did you see something?”

“What do you care?” she retorted.

“Alone, you’re nothing,” he said. “What did you see?”

“I know where they are.”

“I don’t see anything.”

“I didn’t say I saw them. I said I know where they are.”

The rivener looked back at the receding V. “If this is a trick, Sykeet…”

“Come with me if you want to save them.”

“You’ve got gall, telling me what to do. I’m the one with a harpoon. You’re no more use in a fight than a fledgling.”

“You were flying in the wrong direction.”

“No one knows where they went.”

“I know.”

“Because you saw a feather on the waves?”

“Come or don’t come.”

“If you know where the pod is, you need me. Alone, you’re nothing but bait. What’s the point of that? Just drown yourself now.”

Sykeet held her anger. The important thing was to save Kyree.

“I’ve gone with a knight against an Alpha,” he said. “Harpooned one of the necks, then got clear while the knight attacked the other head. It takes strength and speed and skill. You have none of those.”

Though she ignored him, he stayed with her. She beat her wings, heading for the double spire, watching the dark green water below for feathers. She saw only silver flashes of fish below the surface. The vision had seemed real, but where was the proof?

He flew closer, not trailing as if he planned to rejoin the knight’s V. He wanted the reward and was betting she’d lead him to it.

“You came when none of the others did,” he said. “Either you know something or you’re grief-crazed. Which is it?”

“Both.”

“No. It’s one or the other, but you haven’t figured out which yet. Hens never know their own minds. That’s the fault of laying eggs.”

Sykeet clamped her beak shut, saying nothing. She needed him to help save her daughter.

“Since you know nothing of fighting, I’ll explain. This-” He swung his harpoon up by its rope, catching it deftly in the talons of his other leg. “-is a bladed harpoon. Not the same as a barbed harpoon. You’d hurl those at Yantay offspring, to keep them from diving. But an Alpha never dives. The blade pierces like a beak and comes out again just as easy. So you can strike again and again, at either head. You follow me?”

She nodded, to keep him from repeating.

“If this was a defensive raid, we’d go in with barbed harpoons, spear a few of the offspring, and retreat before the Alpha could reach us. But I’m betting an Alpha knocked down the net and took it. Attacking an Alpha is harder. Especially when there’s only one of us.”

The rivener wasn’t very good at counting. But he had a harpoon, which made up for it. She focused on the sea. The double spire stood up from the waves ahead. She hadn’t spotted a pod. An Alpha should be easy to spot with its serpentine body undulating on the waves. And sometimes the offspring breached with a splash.

He interrupted her thoughts. “How do you know?”

“What?”

“How do you know where the fledglings are?”

“I saw the pod near the double spire.”

“Before you got here?” His voice changed, dripping disgust. “By flying with the dead in the clouds?”

She wished she hadn’t answered. This could take a dangerous turn. “Just a dream,” she muttered.

“You led me here because of a dream?” he shouted.

She tried to calm him. “I followed the net down during the storm. I spent the night clinging to the rock in the cold. Then I saw.” Better to say no more.

“How could you see in the dark?”

“I could hear.”

“You heard nothing!” he bellowed. “You foolish hen! You led me from the real hunt only because of your imagination.”

“Then go back!” The words were out before she could stop them.

She saw a white splash ahead, past the twin spires. She tried to see details with her huntress eyes, but the splash was gone. A breaching?

“To the right of the spire,” she said.

“What? Your dream?” he railed. “Your imaginary pod?”

Sykeet saw what might have been a rolling log with a branch sticking up. No, two branches.

“The Alpha,” she said.

There was another breaching near it. The rivener must have seen. He hooted and swooped down, low above the waves.

“They won’t have spotted us yet,” he said. “They can’t see like I can.”

She heard the eagerness in his voice, the thrill of the hunt.

“I have to plan this,” he said. “Only one of us, so only one chance.”

He seemed to be talking to himself.

“The sun’s behind me,” he said, “so they’ll see my shadow just before I strike. If this were a defensive foray, at least two of us would dive, a harpoon for each head. But it’s just me. Wait – you. You could feint for the second head. Can you do that?”

“I can do anything for my daughter.”

“Just be bait. Even a hen can do that. Fly as close as you can, otherwise both heads will attack me, and there’s no chance of saving the Prince.”

He was only thinking of the Lord’s son, none of the others.

They skimmed low over the sea, wingtips practically touching the waves with each downbeat. Sykeet was panting to keep pace with the drake’s huge wings.

The Alpha’s body undulated atop the waves. She could make out something on its back. That must be the crèche net, stretched like a web beneath its dorsal spines. The Yantay’s long necks swayed, heads bobbing ahead. Sykeet was too far away to detect motion in the net. Was Kyree still alive?

She remembered Kyree crawling in the net in the aerie, tiny wing and hind talons clumsily climbing from strand to strand each time Sykeet came to feed her. She remembered her delicate, almost transparent wings covered with soft, immature feathers. The net that had supported her was now her prison. If not her tomb.

“Three, four, five!” announced the rivener. “Five offspring around the Alpha. He gripped his harpoon with his right rear talons, rope in the left. “Bad to worse. And no chance of just pulling the net off the spines. It’s stretched tight. Have to cut it loose. Do you see the Prince?”

There was someone in the net. She couldn’t tell who. But she saw motion, a beak through the net. She resisted the urge to call out to Kyree.

“Time for strategy,” said the rivener. “I’ll strike at the right head. Unless it turns. Whichever I choose, you have to distract the other. Get in close enough for it to strike at you.”

Close enough for it to kill me, she thought.

There were at least three fledglings in the crèche net. Corpses, too: bloody remains of bones and feathers. The Yantay were taking their time, relishing their feast. Rage boiled inside her. Rage that could get her killed without saving her daughter.

The rivener’s long wings beat slow and steady. Sykeet’s were faster, frantic.

“Get ready,” he said.

One of the offspring’s heads turned, spotting them. It trumpeted, and other heads turned toward it.

The rivener beat his wings faster, diving in just as the Alpha’s heads turned toward him. He veered right, hurling his harpoon at the last moment. The blade plunged into the Alpha’s neck with a solid thud. He hung onto the harpoon rope, swinging the head sideways. Both heads trumpeted, then there was a crack of breaking vertebrae.

The other head was arcing toward the rivener when Sykeet swooped in, tail and hind feathers fanned out with a sudden “whump” of braking air.

The Alpha was startled, recoiling, and she collided with the head. Its jaws snapped on her tail feathers, and she gouged the single huge eye on its head with her beak.

It screamed, releasing her tail, and she beat her wings, desperately climbing into the air above it. Lost tail feathers swirled below her.

The remaining neck had collapsed at an unnatural angle across the Alpha’s back, spasming. The rivener landed on it. Tugging with the talons of both legs, he pulled loose the harpoon.

The other head should have been blind, but the neck curved toward him.

“I told you to distract it!” he roared. He flew toward the net stretched between the dorsal spines.

Sykeet glimpsed Kyree trapped in the net. Her daughter was alive! She swooped fiercely at the Alpha’s head, ripping loose scales with her talons. The jaws lunged toward her, just missing her pinions. The eyeball welled with blood. How could it still see?

She flew to the back of its neck and dug in with her hind and wing talons as it bucked. She bit deeply with her beak, tasting blood.

It hurled her free, and she tumbled in the air, barely gaining control above the waves. The Yantay offspring clustered around it, heads weaving dangerously near her, jaws snapping.

On the Alpha’s back, the rivener used his harpoon to hack at the net strung between the dorsal spines. The remaining head swung toward him again.

This time, Sykeet flew directly below the jaws, talons-first at its throat. She tore at its windpipe, and blood spurted. Air hissed from its torn throat as its roar of fury lost breath. She hung on with her talons, wings flapping for balance as the neck thrashed. The serpentine body below jerked, entering death throes. She had a sudden fear it would sink, carrying the crèche net into the depths.

The rivener had trouble cutting the cords with the bone harpoon. But as Sykeet hung on, she saw him drag free a struggling fledgling.

“Time to go,” he said.

He had the Prince.

“No! The other fledglings!” she shouted.

“I can’t fight all the Yantay.” Holding the Prince in his talons, he took flight. His harpoon dangled beneath one leg.

Kyree and another fledgling were still trapped in the net on the back of the dying Alpha. Blood jetted from its artery onto her feathers.

She dropped from its neck, beating her wings furiously as she pursued the rivener. He flew over the waves with slow, powerful strokes, carrying the Prince.

As she caught up, she turned her beak sideways and snatched the rope with the harpoon. She yanked. It jerked from the rivener’s talons. He swore, losing the rhythm of flight.

She veered back toward the pod. He shouted after her, but he had the Prince. He wouldn’t risk his reward for the sake of a harpoon.

She landed on the back of the Alpha as its head collapsed onto the waves with a splash. In the crèche net were Kyree, watching her with trust in her eyes, a crying fledgling she recognized as Toosa, and the mostly-eaten remains of the others.

The Alpha’s corpse was at the mercy of the waves now. The long body with its dorsal spines rocked from side to side, threatening to roll over. Sykeet shifted her grip on the harpoon.

Abruptly the net jerked back toward the Alpha’s tail.

She turned to see one of the Yantay offspring gripping the net in the jaws of both heads, dragging it into the sea. She tried to pull back, but her hollow-boned weight was no match. And the dorsal spines, once stiff on the Alpha’s back, had relaxed in death, offering no resistance.

She took flight, flapping toward the offspring by the tail.

She didn’t trust herself to throw the harpoon. She flew directly at the Yantay that gripped the net, wings beating furiously as she slashed with the bloody harpoon.

The Yantay trumpeted, releasing the net from both jaws. She kept flying at its heads, stabbing as the necks tried to weave out of the way. Blood sprayed over her feathers.

The Yantay dove to escape, but another lunged toward her, grabbing her dangling harpoon rope. As it pulled her toward it, she plunged the harpoon into its eye. It let go with a scream, and as she jerked the blade free, the Yantay dove beneath the waves.

Now there were only three of the offspring on the surface, necks weaving, heads trumpeting, wary.

She landed on the Alpha’s back and pulled at the net with her talons, unwrapping cords tangled around the fledglings. Then she feverishly sawed at the net, hacking through another cord.

Kyree and Toosa struggled out just as a Yantay pulled on the net. She let go of the harpoon. Grasping a fledgling with each leg, she beat her wings, lifting off from the rolling Alpha. Her heart hammered as she struggled above the blood-streaked waves, flying back toward the rookery.

Me and My Heart

By Anton Rose

I meet the man in a hotel outside of town. Room 304, just like he said. He’s there when I arrive, watching football on the television. “Shut the door,” he says, and I do.

He opens a briefcase and shows it to me: seven ounces of flesh suspended in liquid and plastic. “We good?” he says.

I reach into my purse and unfurl the bundle of money. Six hundred pounds, made up mostly of fives and tens, scraps of cash collected over the months, small enough to avoid drawing any attention.

We make the exchange, and the man walks towards the door.

“Wait.”

He stops.

“I don’t know how to do it.” I hesitate. “Can you help?”

“It’ll cost more.”

“How much?”

“Another two hundred.”

“I don’t have that much.”

He sighs. “How much you got?”

The forty pounds left in my purse is for groceries, but I can worry about that later. I hold it out to him.

He takes it, opens his briefcase, and finds a bottle of clear liquid with a syringe. “You got a knife? Needle and thread?”

“Yes.”

He passes me the bottle. “Use this before you begin. Rest’s up to you.”

When I get home, it’s ten o’clock. I should have an hour before my husband gets back. I work quickly, checking diagrams on the internet before injecting the liquid into my side, just above one of my bruises. I use a kitchen knife, sterilised in boiling water. It stings at first, but the injection takes most of the pain away. I slice and carve with the knife, using a mirror to guide my trembling fingers until I make the final cut. For a moment, my senses plummet and the room feels darker, smaller, like all the texture has been buffed off the edge of the world. I make the switch.

He could be home any minute. I stitch myself back together with needle and thread, and it’s only then that I realize I haven’t thought about what to do with my old heart. I bury it in the garden.

I wait for the thump of his footsteps on the staircase, the sound of him fumbling at his clothes and climbing into bed. The smell of his breath, stale alcohol and smoke, his fingers in my hair and on my body. But the door never opens.

In the morning I find him asleep on the sofa. There’s a beer can on the floor, and a pool of sticky liquid where the dregs have drained out. I clean it quickly before making breakfast, and when he wakes he’s in one of his good moods, so things are okay.

When he leaves for work, I examine the stitching. It’s already healed. The lines I drew with the knife have come back together, and my new heart beats underneath.

Things feel different now, like someone has turned the volume down by a couple of notches, like they’ve gone into the settings and fiddled with the contrast.

In the garden, a flower has grown on the spot where I buried my heart. There’s a single rose at its head, red like blood.

The rest of the week is okay. I keep to my normal routines, making sure the house is clean and dinner is on the table when he gets back from work. The days blur into each other, a steady grey.

One day he throws a plate at the wall. It takes ages to clean all the grease, but I know he doesn’t like his meat cooked that way so it’s my own fault, really. He apologises later.

In the evenings, while he sits on the sofa watching television, I bring him drinks but I keep the pace slow so he never goes beyond the dulling stage. He touches me in bed, but if there are any marks still left on my chest, his groping fingers don’t find them. On Friday he comes home with flowers and a bottle of my favourite wine. The weather is fine so we eat outside in the warm air. I try to enjoy the wine but it doesn’t taste of anything. While we sit there he says it reminds him of one of our earliest dates. I see the rose in the garden and I wonder.

On Saturday night he goes out with the guys. He kisses me when he leaves, but when he returns in the small hours he slams the door and I know it’s time. He swipes at me clumsily, but when he tries to grab my arm his sweaty fingers slip and I escape into the kitchen. I grab a knife with one hand, the cordless phone with the other. I tell him to leave.

He smiles stupidly and slurs his words. “Come on, baby, why all this?”

In my chest, my heart is steady. “If you come near me, I’ll use this knife, and if you don’t leave, I’ll call the police. I mean it.”

“You’re feisty tonight, eh?”

I begin to dial the number.

He holds his hands up, smirking. “Okay, okay …”

When he’s out the door, I put it on the latch and speak through the gap. “I don’t want you to come back. Not ever. It’s over. I mean it.”

He laughs. “You can’t live without me, honey. You know that, and I know that. We love each other. We need each other.” He walks away. “I’ll see you soon,” he says.

When he’s out of view, I close the door.

He thinks it’s going to happen like all the other times. He’ll come back grovelling, tell me how much he loves me. That he’s sorry, that it will never happen again. And I’ll take him back.

He’s wrong.

This time the locksmith will be here in an hour. This time I’ll change my details at the bank. This time I’ll go to the courts, get one of those orders. And this time I won’t feel anything.

These Old Hands

By Jamie Killen

Frances heard a shriek as she approached the cottage door. Joseph hovered outside the threshold, twisting his cap in his hands. “She’s bad, Frances. Says she can’t take the pain.”

The old woman gave him a dismissive wave. “Ah, she’ll be fine, lad. It’s nature’s way.”

“What should I do?” He was barely more than a boy, less than a year married. His face, normally nut brown from working in the fields all day, had a grey cast to it.

Frances shouldered past him, Margaret right behind her. “Just stay out of the way, boy, and let us work. I’ve never lost a baby nor a mama yet, and I don’t intend today to be my first.”

Inside the cottage was dark, air thick with the smells of smoke, sweat, and urine. Frances could dimly make out Essie’s form writhing on the small bed against the far wall. “Margaret, get the window open and put on water to boil,” she said, rummaging in her bag of supplies. The packets of powders and herbs went on the cottage’s rickety table; Margaret would know without being told how to mix them.

Frances carried the birthing stool and linen to the bedside. “Now then, young Essie, let’s have a look at you.”

Essie’s round face glistened, her cornsilk hair flattened against her scalp. “Oh, Frances, it hurts something terrible. I think something’s wrong.”

Frances pushed back the blanket and peered between Essie’s legs, pressing one hand against the swollen belly. “Nonsense, girl. Your mother said the same thing when she birthed you, and you were no trouble at all. We’ve time yet.”

While Margaret boiled water and brewed the herbs, Frances got Essie out of bed and on her feet. At first she resisted, but Frances eventually got her to walk a circle around the small room. When Essie’s next labor pains struck, the old woman helped her sink into a squatting position on the low birthing stool. “Margaret, hold her up.”

Margaret set aside the cup of brewed herbs and moved to support Essie’s lower back. She was a thin, fragile-looking girl, but Frances knew she was far stronger than she seemed, and holding up Essie’s limp weight posed no challenge. Frances eased down onto one knee, wincing at the stiffness in her bad hip. Pushing up Essie’s skirt, she leaned down to check her again.

At first glance, it appeared to be the start of a normal crowning. The lips of the vulva were stretched over a round, smooth surface, one a little bigger than a balled-up fist. Then Frances frowned and took a closer look. It was the right size to be the baby’s head, true, but it was too dark, too shiny. Even if Essie had been bleeding, it wouldn’t have stained the scalp that deep, gleaming black.

When Frances leaned up, Margaret’s sharp brown eyes were watching her. Breech? she mouthed from behind Essie. The midwife shook her head.

“Essie, bite down on this, now. I’ve got to reach in.” She passed Margaret a leather strap and smeared her fingers with goose grease from a small jar.

Essie tensed and let out a groan when Frances slipped her fingers past the mass. Frances felt around the sides of the object, pulse quickening with each moment that passed. The shape her fingers traced was a smooth ovoid. No limbs, no face, no bones. In place of soft, yielding flesh was a slick carapace or shell, hard as stone under Frances’ fingers. As she explored, there was a flutter, some tapping from within, a pulse or a kick.

“What is it? What’s wrong with him?” Essie’s voice came out shrill and garbled around the strip of leather.

Frances forced herself to meet Essie’s eyes. Poor girl, she thought. And it’s her first. “We can’t know till you’ve birthed,” she said, and could see that Essie was too scared to ask again.

The rest of the labor Frances handled like any other, instructing Margaret to rub Essie’s back when the pains came, applying salve to prevent tearing and blood loss. When the time came to push, Margaret moved to ready the linens. Frances watched her face, could see the shock pass over her features when she saw what was coming out. But then the girl steeled herself and looked away, busying herself with preparations. Frances took Essie’s hand in her own arthritic fingers, not allowing herself to wince no matter how hard the girl squeezed.

It came out smoothly, and Frances could see right away that Essie was in no danger. Margaret caught it as it slipped from between Essie’s legs, a perfectly even, black shape, like obsidian with the edges smoothed away. There was no cord, nothing attaching it to Essie’s body. Margaret’s hands trembled as they held it, her throat working as she swallowed convulsively.

“Why isn’t he crying?” Essie gasped. “Why isn’t he crying?”

She leaned forward and saw what she had delivered into the world, and the scream that ripped from her throat seemed to pierce Frances down to her bones.

By the time Frances and Margaret emerged from the cottage, Father Godfrey and the steward had arrived and stood waiting with Joseph. The sun, which had been high when Essie’s labor began, touched the horizon. “Well, is it true?” the steward demanded.

“Is what true, Master Hugh?” Frances asked, unable to conceal her irritation.

“That there has been a demon born here.” He was a short, stocky man with rough peasant’s features but an immaculately trimmed beard and a fine wardrobe. His pale face reddened when he was angry or nervous; at the moment he appeared nearly purple.

“What about Essie? Is she ill? Can you not help her, Frances?” Joseph pleaded.

Frances patted the young man on the arm. “She’s had a shock, but she’ll live. We gave her medicine to calm her and help her sleep.”

Joseph shifted from one foot to the other, eyes darting toward the cottage door. Father Godfrey cleared his throat. “And what of the… the birth?”

Frances turned to Margaret. The girl held a basket in front of her, awkwardly, not letting it touch her body. She set it on the ground and took a hasty step back. Frances reached down and lifted the soiled cloth to reveal what lay inside.

“Mother of God,” the steward breathed. Father Godfrey made the sign of the cross, eyes wide. Joseph, seeing it for the second time, let out an anguished gasp and moved a short distance away from the rest of them.

It lay cushioned by linens as though it were a real child. Dotting its surface were flecks of blood and mucus, residue that Frances would have cleaned off of a normal baby but could not bring herself to do now. As she pulled more of the cloth away to reveal it entirely, it gave a little twitch.

Hugh darted back as if it had sprung at him. “What is it?”

Frances pursed her lips, shifting to her good leg. “You think I know?”

“You’re the midwife. You delivered the thing. How can you not know what it is?”

“Well, I know it’s no baby,” she snapped.

Father Godfrey inched closer and bent over to inspect it. The hem of his cassock trailed in the dust before his feet. “Has it been moving since the birth?”

“Since before,” Margaret murmured. “We attended to Essie throughout her pregnancy and always there was kicking. What we thought was kicking.”

“Clearly, it is of the devil,” the steward interjected.

“Ye’re an expert on devils now, are ye?” Frances muttered.

Hugh shot her a poisonous look and turned to Father Godfrey. “What is your opinion of it, Father?”

The priest bit his lip, eyes fixed on the thing in the basket. He was a tall, thin man with a face younger than his years. His sandy hair and large grey eyes always reminded Frances of a skittish fawn. “I have never heard of its like,” he said at last. “It looks like an egg, but seems to made of some stone or mineral…”

“Well, we can see that. Could it be that the woman fornicated with a demon, producing this?” the steward asked.

“You shut your foul mouth!” Joseph shouted, rushing toward Hugh. Father Godfrey managed to get between the two men before blows were exchanged. Frances glanced at Margaret, who eyed the steward with undisguised contempt.

“You are obviously under duress, so I will forget that this incident occurred,” Hugh said, adjusting his jerkin. “But it is plain as day that that thing is a source of evil. If it is an egg, then it will one day hatch, and I do not wish to see what is inside. ”

“That does not mean it was Essie’s doing,” Father Godfrey replied, holding up his hands in a placating gesture. “It could be the result of an evil committed against her.”

“Who could perform such a curse?” the steward asked.

None of them spoke. The only sound was the clucking of Essie’s hens as they pecked in the dirt around the wood pile. “Would you have any knowledge of how to perform such a spell?” Hugh stared at Frances as he asked the question. Father Godfrey’s eyes widened and he bit his lip.

“Don’t be daft. I know nothing of spells,” Frances said, lowering herself into a sitting position on the chopping block next to the woodpile. She forced herself to sound bored, secretly wondering if the day had finally arrived, as she always knew it would.

The steward folded his arms. “It is said that no mother or child you have attended has died. Surely the villagers exaggerate?”

To her left, Frances felt Margaret’s body tense. “Tis no exaggeration,” Frances answered calmly. “All have lived, although some do not show due gratitude.”

Hugh’s face darkened further. Frances remembered the day he slid into her arms, blue and still with the cord wrapped around his neck. Two breaths into his sticky mouth and a slap to the arse had forced air into his lungs and set him squalling like any other newborn. Francis wondered now if she should have slapped him harder.

“I’d wager that such success is unknown, even for the most skilled midwife. One might be forgiven for suggesting it might even appear to be sorcery.”

“Frances is a godly woman, Master Hugh. It is not her doing,” Father Godfrey interjected quickly.

“Oh,” the steward said, raising an eyebrow, “you are certain of this?”

“Surely you are aware, Master Hugh, that all midwives must receive the approval of the bishop himself.” Margaret’s voice came out low and mild, but her glare was like frost. “Frances has had permission renewed by three successive bishops, one just last year during his visit to the manor. Do you suggest that the bishop is incapable of identifying a witch?”

The steward’s eyes widened. “I suggest no such thing! I simply–”

“Well, then, let us stop wasting time and discuss what to do with the abomination.” She folded her hands primly in front of her apron. Frances had to feign a fit of coughing to hide her laughter.

Joseph stared at the basket with loathing. “We destroy it. We break it open and kill whatever is inside and burn anything that remains.”

Father Godfrey picked at the front of his cassock. “We are not yet certain that it is of demonic origin…”

“I am.” Joseph strode to the woodpile and seized his ax. The priest and the steward took several steps back, giving him wide berth.

Hefting the ax in both arms, Joseph paused, a hint of doubt in his eyes. Then, shaking his head once, he lifted it over his head and brought it down on the egg.

There was a clanging sound, like the church bell, and the ax bounced back into the air. Joseph staggered back, nearly dropping it. From where she sat on the stump, Frances peered into the basket. The thing appeared untouched.

“Here,” the steward said quietly, holding out his hand, “let me try.”

He met with no better result. “It’s like trying to cut an anvil!” Hugh gasped, rubbing his right hand in his left.

“Perhaps…” Father Godfrey fished a small vial out his pocket, recited a prayer, and dribbled holy water over the black shell.

They waited. Margaret reached down and nudged it with one knuckle. “I feel no movement.”

Frances hauled herself to her feet and touched it with the toe of her shoe. It immediately began to twitch, rocking back and forth within the basket.

“It seems to respond only to you.” Hugh said quietly, eyeing Frances. Nobody replied.

By the time full night had descended, they had determined that neither blades, nor fire, nor the touch of a crucifix could kill what had emerged from Essie’s womb. Frances’ back ached from sitting so long, and she shuffled back inside the cottage to check on Essie again. The girl still slept; Frances had given her enough tincture of opium to ensure that she would not wake until morning. She had no signs of fever or infection; Frances wondered what illnesses could arise from birthing such a thing, and if she would be able to help if Essie showed symptoms.

Back outside, the steward and the priest argued about what to do with the thing overnight. “It cannot come into the church!” Father Godfrey protested.

“Well, it cannot be left here. And it certainly will not be taken to the manor,” Hugh objected.

“We should have the bishop’s counsel,” Father Godfrey fretted.

The steward sighed. “A message will not reach him for two days.”

Finally, they agreed that it would be locked in a chest and buried until they received instructions from the bishop. Father Godfrey set off to the church to fetch a chest while Joseph and the steward stood guard. “We’ll be on home, then,” Frances announced, climbing to her feet with a groan. Hugh looked like he wanted to object but held his tongue.

Margaret laid a hand on Joseph’s shoulder. “We’ll be back early to tend to Essie.”

He nodded, defeated stare fixed on the egg.

Margaret and Frances said nothing on the walk back to their hut. Once inside, Frances settled in front of the fire with a long sigh. The hut was small but well-built, with bundles of dried herbs hanging from its low ceiling. It smelled of rosemary, onions, and the rabbit stew they had left simmering in the hearth when they left. Margaret lifted the lid of the stewpot and stirred its contents with a ladle. “Perhaps it is not wise for you to anger the steward so,” she murmured without looking at Frances.

“Hm. I could get on my old knees and kiss that bastard’s boots, and he’d still think me a witch.”

Margaret said nothing until they finished their meal. “He was right about something. It responds only to you.”

“Aye,” Frances said quietly, adding a stick of wood to the dying embers of the hearth.

“Could it be,” Margaret began slowly, “that it is not Essie who is the target of malice, but you? How better to strike against a midwife?”

Frances said nothing. Half of her hoped that Margaret’s wits failed for once and led her to the wrong conclusion. The other half wanted to tell her.

Margaret continued. “But there is no one in this village who you have angered, besides the steward, and I doubt that such a boorish fool would have the knowledge for magic. And no one could find fault with your midwifery; everyone knows that many children and mothers would die without your skills.” Her sharp features radiated intensity. “So the question is, who would benefit from stillbirths and women dying in labor?”

Frances gazed into the hearth. She could feel Margaret watching her. “It’s not all skill,” she said at last. “A lot of it is, mind. I learned my trade well, from one who knew it well. But there’s more to it. These hands…” She smiled bitterly and gazed down at her fingers, gnarled and twisted as the roots of a tree. “These old hands, they can conquer demons.”

“The first time was me fourth birth. I remember it well…

I was still young then, still apprenticed to Old Hannah. I knew much already, all of the herbs and elixirs, knew when it was proper to use feverfew and ground willow bark. I could see when there be twins and know the place of the unborn babe in a mother’s belly. But I had not yet delivered a baby on me own, and the thought of managing without Old Hannah scared the life out of me.

This time was a hard labor of a woman who had birthed five times before, with only one baby living. Her pains lasted through the night and into the morning. By the time she was ready, she was almost too spent to push, wouldn’t until Old Hannah gave her a good talking to.

I myself hadn’t slept. Bone-tired, I was. I didn’t even know the baby was coming out until Old Hannah gave me a slap and told me to pay attention.

It was without breath when it came out into Hannah’s hands. But I could see it had no cord around its neck, knew it had moved only hours before. Knew it should live. Old Hannah tried to bring it back, flipped it over onto its tum and gave it a smack on its back, but it still didn’t breath.

When Old Hannah turned the little body over on its back, that’s when I sees it. At first I thought it was a caul, but a caul wouldn’t be black. It was something alive, something black fixed on the baby’s face, like a little patch of black fog. There were no eyes or arms that I could see, just a wee mouth, and it had it around the baby’s.

I was scared out of me wits, I don’t mind telling you. I screamed like a fool and backed away, but Old Hannah didn’t even see it. She just yelled at me to bring the bag, stop being such a ninny.

I knew why she wanted the bag. She’d given up on the poor thing, needed the holy water to say the sacraments since there was no priest. Well, I wasn’t having that. I didn’t even think about what I was doing, I just stepped over and ripped that evil thing from the baby’s face. It fought me fierce, it did, tried to stay stuck to his little mouth, but I got the best of it. The moment I got it off the baby, it just broke apart, turned into soot and dropped all over the floor.

‘What are you doing?’ Old Hannah asks me, spitting mad. I ignores her, for once, and touched the baby’s chest. Didn’t know why, just that I had to. I felt something, something moving between me and it, and then its eyes opened and it started to cry.

“Old Hannah saw it happen. She looked at me like I was the Holy Virgin her own self. But we never talked of it, not once until the day she died. I’m no witch, you see. There’s no spells or deals with the Devil. But when a child is born dead, I can bring it back. And when it is born with one of those demons…”

“You destroy them.” Margaret’s eyes were wide. She was silent for a moment. Then: “This is not a skill that can be taught?”

Frances covered the girl’s hand with her own. “No, child. I don’t even understand how I do it.”

Margaret took a deep, shaking breath. “And when you are gone and I am village midwife, children will start to die again.”

“Yes. Not many. Ye’re a good midwife, Margaret, better than I ever was. Better than Old Hannah, even. But there’ll be some with demons, or ones who are beyond teas and medicines.”

“And I’ll be powerless to save them.”

Frances was silent for a time. At last, “Ye’ll save more than ye lose, girl. That’s what you must remember.”

She waited while Margaret cried in silence, just a steady drizzle of tears trailing down her stony face. When the girl was finished, she let out one heavy sigh, wiped her cheeks, and began tidying up after their supper. “You believe the thing Essie birthed has something to do with the demons you’ve thwarted?” she asked, scrubbing one of the bowls.

“Don’t see any way around it. It don’t look like one of em, but it has the same feel.”

“But this one survives your touch.”

“Aye. They found a way to send something I can’t kill. I think it’s the shell keeps it safe.” Frances stood and shuffled over to her pallet. “I’ll sleep on the matter. Tomorrow we’ll decide on what’s to be done.”

Frances woke before first light. At first she thought it was the throbbing ache in her joints that had woken her, as happened most days now. But her heart pounded and there was the tang of fear in her mouth; she made herself still and listened for what had broken her sleep.

There. Something rustled outside the door. Frances rose as quietly as she could, slipping past Margaret’s pallet. She found their one carving knife and gripped it in her trembling fingers. Pausing with her hand on the latch, she listened for what lay beyond the door. All was quiet.

Before she could lose her nerve, Frances lifted the latch and flung open the door, knife ready.

The egg lay on the ground outside the hut. As Frances took a cautious step toward it, it began to rock back and forth. Even while standing several feet away, she could hear the sounds emanating from it. These sounds weren’t weak clicks and stirrings, as before; now it was a hard, steady series of taps, a chisel on stone.

“Frances?” Margaret’s sleepy voice drifted out from the hut.

“All’s well, Margaret. Stay inside.” Frances tore her gaze away from the thing, fixed her eyes on the smear of heather grey where the sun would soon spill over the horizon. She wrapped her shawl around her shoulders and held her arms closer to her body in an effort to ward off the morning chill. Winter was coming on fast, she knew, but at that moment she realized that she would never see another snow. That’s something, at least, the old woman thought with a grim smile.

Margaret appeared in the doorway. “How…” she breathed.

“Impatient little thing, isn’t it?”

“Should we–”

“No.” Frances cut her off. “Breakfast first. We’ll deal with this thing after we’ve eaten.” As she shuffled back to the hut, Frances aimed a solid kick at the egg, sending it rolling across the garden.

As instructed, Margaret prepared a hearty breakfast, far larger than their usual meals. Bread with honey, cheese, bacon. Frances ate slowly but finished everything in front of her. Margaret merely picked at her food.

“The steward will find the box unearthed and empty. Do you think he will think to look here?” she asked at last.

Frances shrugged.

“Before, we could deny that it was anything to do with you,” Margaret pressed. “But since it has come here… What if Father Godfrey changes his mind, begins to think you a witch?”

Frances let out a laugh. “Godfrey’ll never turn on me. He knows I know too much.”

Margaret raised a quizzical eyebrow. Frances leaned close and lowered her voice to a dramatic whisper. “Next time you see young ones playing in the village, see if you can spot the one who has his eyes.”

Margaret’s mouth dropped open, but she said nothing.

Frances continued. “That bloody Hugh, on the other hand…”

The tapping outside grew louder. Margaret rose and peeked outside, opening the door only a crack. “Frances,” she said, voice tense.

Pulling the door all the way open, Frances squatted down to examine the egg. There was a tiny hole, scarcely bigger than a pinprick. Something sharp and white emerged from within, chipping and scraping until another tiny piece fell away.

“That’d be the egg tooth,” Frances murmured.

She stood. “Margaret, Essie’ll need checking. Go to her and make sure there’s no fever.”

“I’ll not be leaving you alone with this!” Margaret protested.

“You’ll do as you’re told, girl.” Frances said the words sharply, though it pained her to be harsh with the girl.

Margaret bit her lip and slowly started gathering her supplies. Frances watched her in silence for a moment. “It’s Widow Cavendish. The one what had a child by Godfrey. He had me convince her to remain silent, but she’d speak if the story needed telling. And Master Hugh bedded the lord’s daughter. She came to me and I gave her what she needed to kill it in the womb. But you must speak of that only if Hugh makes an accusation, only if it means your life.”

Margaret slipped the bag over her shoulder. “Why are you telling me this?”

“All my secrets are yours now.”

“What will you do?” she asked quietly.

Frances crossed the room and embraced the girl. “Only what must be done.” She patted Margaret’s cheek. “Don’t you worry. This old woman’s got a trick or two yet.”

Tears welled up in Margaret’s eyes. “Frances, please…”

“Go now. Off with you.” She waved a hand at the door.

Margaret hesitated, opened and closed her mouth. Finally, taking a deep breath, she walked out of the hut and started on the path to the village. Frances waited until the girl disappeared over the hillside before gathering her things.

By the time Frances approached her destination, her lungs burned and her clothes were damp with sweat. “Right pain in the arse, you are,” she puffed, dropping the basket in the grass. “Making me walk all this way.”

She settled on the ground to catch her breath. Below her stretched the rocky valley north of the village. Just one or two paces from where she sat, the ground dropped away into a crumbling granite cliff face. Peering down, Frances caught sight of the stream running along the valley floor. She remembered walking there, once, when she was young. It had been a long, difficult journey to the bottom of the valley, but there had been sun and cool water and a boy she might have wed had things gone just a bit differently. Smiling, Frances let herself linger on that memory.

The sound of the thing in the basket broke her out of her reverie. There was a crack as a large piece of shell gave way, revealing something darker moving inside. A black, jointed limb reached out, grasping, but it could not yet escape.

“Five hundred and fourteen,” Frances said. “That’s how many babies I’ve helped to be born. And those ones grew up and had babies themselves. There’s little ones today whose mothers and grandmothers I’ve looked after. Never had none of my own, but I’ve still brought more life into this world than you can imagine.”

There came a snarl from the basket, egg rocking back and forth as another piece of shell fell away.

“And that,” Frances continued, “is something I won’t let anyone undo. I don’t know where ye’re from, but I know you was sent for me, and that must mean you can kill.

“But ye know what else?” She smiled. “An egg keeps a chick safe. Without it, the poor thing’s helpless. If ye had to hide in such a strong shell, it must mean you can be hurt.”

One side of the egg crumbled. Another limb stretched out, dragging a leathery wing along with it. Frances rose to her feet.

With one last, shuddering spasm, the shell broke apart. A dark, spindly shape launched itself out of the basket, speeding toward Frances. She caught sight of the wings, and teeth, and legs, too many and too long. Then it was upon her, serrated fangs sinking into the flesh at her throat. Run, her body screamed, fight! But she forced herself to take hold of its wings, squeezing them tight in her fists. A bone under the stretched skin cracked beneath her fingers, and the thing tried to push away, snapping its teeth and shredding the skin of her chest with its claws. Frances felt liquid warmth flowing from her neck down to the ground, knew the pain was soon to follow.

“These old hands, they can conquer demons,” she whispered, and, holding the creature to her breast like a child, she stepped off the edge.

We Are Stardust

By J. M. Evenson

I.

If Lily could’ve strangled Susannah, she would’ve. Unfortunately people were watching.

“You were looking at my boobs,” said Susannah. They were standing in the locker room. Three shorter girls circled Susannah like wolves. Susannah was naked apart from her lace panties, and she had Lily cornered.

“I already told you, I wasn’t,” said Lily. Actually, she kind of was. They were ridiculously huge. Also, Susannah was standing right in front of Lily, so there was nowhere else to look.

“Oh my God, why are you lying?” said Susannah. “It’s natural to be curious about the human body.” Susannah was both cunning and vain, a mixture that had become toxic when she hit puberty. Her weapon of choice was sarcasm. Susannah never, ever meant what she said. “I mean, it must be hard for you. Everybody knows you’re delayed.” Susannah let her voice linger on that last word as she looked at Lily’s training bra. It wasn’t even half filled.

A crowd grew as the four girls closed in around Lily.

“We’ve all been there,” said one of them.

“Trust me,” said the other.

“If you have any questions, sweetie, just let us know, okay?” said the third.

Crimson circles scalded Lily’s cheeks. “Leave me alone,” said Lily.

Susannah dug a finger in Lily’s underpants to look and let it snap back. “Holy shit, she’s smooth like a Barbie!”

Susannah was lying. But it didn’t matter. Everyone laughed. The sound of it ricocheted off the lockers.

That’s when Lily punched Susannah. Hard.

Susannah reeled backward and the four girls crumpled into a pile of screams.

Lily grabbed her clothes from her locker and crammed her legs into her pants. It wasn’t like she was going to be able to explain why she’d punched Susannah to the principal, so there was no point in hanging around to see what kind of punishment they were going to dole out. Lily’s hair was still wet when she slung her backpack over her shoulder and left the school.

The weather outside was overcast and hot, no different than most winter days in her small Ohio town. Most of the kids took the magnet home to avoid the swelter, but Lily liked walking. After the Great Warming, January was pretty much the only time she could do it anymore. They’d already had to move north twice. If the heat continued to rise, they’d have to do it again. At least they were part of the lucky few who had the money to do it. As she turned down the avenue, Lily eyed the dark clouds gathering overhead, promising a sandstorm.

The worst thing about all of it was that Susannah was right. Lily was delayed. She was almost fifteen, but her body had hardly even started developing. There was something, though — she couldn’t tell what — that made Lily think things were just about to change. For three days she’d felt weird. Not nauseous, exactly; it was more like a heaviness had taken over her limbs, then worked its way inward, settling squarely between her hips.

Lily was still steaming about Susannah when she noticed sunlight echoing from the surfaces around her, illuminating the street with a piercing yellow. She paused to look up.

It had just been cloudy a second ago. Now the sky was perfectly blue. When she reached up to shield her eyes, she saw something stirring in the sunlight — it was a dust of some sort, filtering down from the sky. Its descent was slow, but it fell straight down, pattering around her like a gentle rain. Her body seemed to cool as she watched it.

Lily opened her hand, trying to catch some of the dust so she could have a better look, but most of it slipped away. When she finally held still, it settled on her palm. Each speck seemed to glow from the inside, shimmering and twinkling as if she’d caught a handful of stars. She reached out a finger to touch them. Constellations appeared, then whole galaxies — her own private cosmos.

Then she noticed: these stars were moving — squirming and expanding, a universe in motion. Suddenly they began to gather into small, worm-like shapes. They were still moving, only now they were a thousand glittering maggots fighting for space. Lily’s hand began to tingle, then burn. With a flash, the worm-like shapes burrowed into her skin and disappeared. Clouds instantly folded over the sky, and it was overcast again.

For one minute, three minutes, maybe a hundred minutes, Lily stood motionless, trying to process what had just happened. For a second she even wondered if she’d imagined the whole thing. That’s when she felt it: the slow wet breaking between her thighs, the dam loose. A blood-stain bloomed in her jeans. Her first.

After that, whenever Lily got her period, she thought about the Day of Enlightenment. It was the day everything changed.

II.

Lily felt different.

It wasn’t anything wild or obvious. Mostly, she was just confused: she never had just one thought anymore; now, she always thought one thing and another thing at the same time. Sometimes the tug-of-war became so violent it felt like the ideas were somersaulting inside of her. She spent the better part of a year combing the information networks looking for guidance on her changing body. Almost all of the articles she found focused on what it meant to turn into a Duo. The only problem was that Lily couldn’t be sure which part of her transformation had to do with the Day of Enlightenment and which part had to do with sprouting boobs.

More distressing, every decision Lily made was now subject to a drawn-out internal debate. Should she eat soy cheese? She could turn that into a half-day argument. There were questions of nutrition and personal need, certainly. Did she require the extra calories? Would that extra food she consumed harm the environment? Was it fair for some people to have access to this particular delicacy, when others did not? She could parse anything for philosophical dispute.

That was the real problem: Lily was now thoroughly, undeniably rational. Her family could tell. Everyone could.

III.

Of course, her mother and brother were proud of their pure-blood status. They refused to use the term “Duos,” instead calling them “Infected” or “Compromised.” If you were infected, at least in the human-only section of the city where Lily and her family lived, it meant ostracism. Lily had to be careful, especially around her brother, Wes.

“I’m leaving,” said Wes. He bit off a piece of toast and watched Lily carefully as if he were evaluating her reaction.

Lily pushed her cereal around in her oat milk. She didn’t have to ask where he was going. She already knew. She flipped the page on her book and continued reading.

“Want to come with me?” said Wes.

“You know I don’t,” said Lily.

“I just thought maybe you’d come to your fucking senses,” he said.

“Don’t start,” she said.

“Or what? You’ll lecture me again about how fucked up humans are?” he said.

Lily rolled her eyes at him. That was exactly what she would do, if he’d listen for more than half a second. But he’d already made up his mind: he suspected that Lily had become a Duo, and he spent the better part of every day trying to get her to admit it.

“Quit reading for a second.” Wes snatched the book from Lily and held it over his head.

Lily eyed him. He was trying to get a rise out of her, to see how she’d respond. It was a test.

She made a grab for the book.

“What is this, anyway?” He scanned the cover. “‘An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation’? What the fuck is wrong with you?”

“I like it,” said Lily.

Wes stared at her hard. Lily could feel her pulse tugging at her collar. He knew. He had to.

He leaned forward and growled. “The world is not a better place with them here, Lily. They’ll turn on us, I promise.”

There were a few ways Lily could go. She could pretend to agree with him, but he’d know she was lying. She could point out the specific benefits of the Duo government, but sensible responses tended to aggravate him and confirm his worst suspicions about her. Or she could do something irrational to prove she was still human.

She tossed a piece of wet cereal at Wes. It hit him square between the eyes.

Wes dropped the book and flung an arm in her direction. Lily swerved before it connected. He lunged for her and caught her by the sleeve. Just before he put her in a half-nelson she let out a shout.

“He’s joining the rebellion, Mom,” she screeched.

“What?” said Sara. Their mother called out from the kitchen. She was in there boiling a pot of English breakfast tea.

“You’re such a dick. I’ll bet you’re one of them,” Wes hissed in her ear.

“Maybe I am. Want to report me to your little buddies?” Lily spat back.

Sara appeared in the doorway. She stood perfectly still, her eyes fixed on Wes. “You’re joining?” she said.

Wes was her mother’s favorite. They were like two heads of the same shark. Whenever they started talking, Lily could hear their circles of approval growing smaller and smaller, like a ripple moving inward: they approved of only pure-bloods, but really only pure-bloods with old-fashioned values, and actually only the two of them. Everyone else was held in self-righteous disregard.

Wes held up his arms like he was trying to soften the blow. “Mom. I know what you’re going to say,” he said.

Sara wound her arms around him. “You’re my boy.”

A smile grew on Sara’s face. A proud smile.

Wes held his stare on Lily.

IV.

The teacher handed Lily a white envelope. Lily’s heart knocked like it was trying to get out.

When Lily opened the letter, she was actually relieved. The letter confirmed what she suspected: she was a Duo. Not only that, she’d tested abnormally high on the rationality scale. She’d spent her whole life feeling like the odd man out in her family, and here was the proof: she was different. Her score meant she was a prodigy, which meant she was special.

The teacher bent over Lily’s desk, her lips pinched into a disapproving frown. “Congratulations, Lily,” she said. Her voice was louder than it needed to be. “I’m sure we all wish you a safe journey to the Government Center.”

There was a sudden silence as everyone in the classroom turned to look at Lily. Their eyes burrowed into her like fish hooks.

It was like a dream — the one where she was naked in school on exam day without her homework and the semi-hot guy she’d had a crush on since kindergarten was laughing at her.

Lily put on her backpack and got up to leave the classroom. Their eyes held fast, casting after her as she left, lining up in the hallway silently to watch her go. She walked slowly, then quickly, and darted out the school doors.

She ran most of the way home. By the time she got home, she could feel the sweat dripping down her spine.

She banged through the door and started up the stairs to her bedroom.

“Lily,” a voice called out.

Lily stopped and turned. Her mother, Sara, appeared in the doorframe. She was holding a highball. Wes slid out from behind her. His face was tight and red.

“The school called,” said Sara.

Lily blinked back tears.

She knew it was irrational to wish she could’ve talked to her mother about becoming a Duo. It was even more irrational to wish she could’ve won her mother’s approval. Lily imagined her mother’s eyes, gentled with devotion, bent on Lily. Her girl, she’d say. She’d hold her in a warm embrace, sway back and forth. But Lily had to be honest with herself. There was never really a chance she would’ve won her mother’s approval, even if she were a pure-blood.

It was one thing to know she wasn’t close with her mother. It was another to know they would never be close.

“I fucking knew it,” hissed Wes.

“I think we all did,” said Sara.

The two-headed shark. Of course they felt the same way. Of course.

Lily nodded. “I’ll go upstairs and pack.”

“That’s probably wise.” Her mother swished her ice and left for a refill.

Lily went to her room and put a few things together, an extra set of clothes and a toothbrush, then came downstairs and left through the front door.

There was no point in turning around to wave goodbye. She already knew no one was standing at the window.

V.

Alejandro was the most beautiful human being Lily had ever seen. Well, partly human.

He had dark hair that fell forward in loose curls. Whenever he got nervous, he pushed his hair behind his ears, revealing dark eyes ringed in lashes that curled upward at the outer corners like a cat’s. He spoke softly and tucked his chin, which, together with his large eyes, made him seem shy and vulnerable.

He lived three doors down in the government center dorms. The kitchen staff was ridiculously experimental in their cooking, which was unpleasant for a picky eater like Lily, but she managed to squirrel away a little of the good stuff whenever it came around. She spent most of her time in the food line watching Alejandro absent-mindedly thumb his bottom lip. Her eyes would inch downward to the dimples of his hips and the tuft of hair sprouting above the zipper of his low-slung jeans. Every time he caught her eyes, she felt a thunderclap of terror and her skin heated to pink.

Lily had only kissed one boy before the Day of Enlightenment. He was a nice guy, but he had super parched lips and refused to wear chapstick. When he leaned in for the kiss, he grabbed the sides of her head to keep it still. He kept every muscle in his face tight, and he didn’t even try to slip her some tongue. The whole thing was rough and dry, like making out with a cantaloupe rind.

But Alejandro was a magical mix of hard and soft. His arms, for instance, were knotted with muscles, and yet they were covered by a downy hair so fine it floated like a spider web. Everything about him was like that: just totally and completely gorgeous. It took Lily six months to work up the courage not to look away when he caught her eyes, but one night, when the kitchen was serving some particularly repulsive fare that involved roasted ants, she invited Alejandro up to her room for cheese and nut-bread from her secret stash.

The conversation started with tales of who they’d left behind and the people they’d been in the days before everything changed. Lily did her best to pretend she’d kissed a bunch of boys and was not in any way an extreme virgin, but she was pretty sure he figured out the truth when she couldn’t remember any of her so-called boyfriend’s names. They talked for hours, until talk gave way to uncomfortable pauses and sweaty palms.

“I think we both know what’s going to happen,” he said, leaning forward.

Alejandro put his hands on her face and drew her close. She could see the shadow of stubble across his jaw, the whiskers slightly raised over a single mole at the crook of his mouth, the soft fullness of his lips that pulled into a natural frown. Lily was suddenly dizzy and hot. He brought his lips to hers as they sank to the floor, fingers clutching at collars and hair, the room tilting, their hot breath interlaced in a kiss. They tugged at their clothes until they were moving as one. A burst of sweetness shook Lily’s body, then calmed to silence.

The silence chilled to awkwardness. Alejandro rolled away and put himself back together again. There were a few words about something he had to do, about seeing her tomorrow, then more silence.

The next day, she saw him in the courtyard. He sat down next to her on her reading blanket and took her hand in his.

“I really like you. You know that,” he said. “But everything in my life is complicated right now. It’s not rational to get involved with so much going on. I’ve got responsibilities here at the center. I have an obligation to keep my head clear.”

He sounded like a stupid B movie.

“I mean, maybe that doesn’t make sense to you. Maybe I’m further along in the hybridization process than you are. You know? I understand the urge to copulate. Obviously, I do. I’m still partly human. But we’re also so much more than that now. We don’t have to be tied down to hormones or whatever.”

‘Tied down’? She’d never really thought of herself as a rope before, but she did want to strangle him, a fat noose around his neck, so maybe there was something to it.

“I don’t want you to think it’s about you. It really isn’t. We’re only seventeen. Maybe in a few years, when we’re both ready to mate and reproduce, we can discuss this again.”

He got up and left.

Lily leaned back on her blanket and listened to her heart bang against the bars of her ribcage, the hollow sound of order.

VI.

Something had to be done about the rebels. Something drastic.

When the rebels bombed the magnet stations in New York and Boston, Lily had been called to sit on the daily meetings at headquarters. They’d picked her because it turned out, after a great deal more testing, that Lily had a gift for tactical strategy. So they made her an official member of the Countermeasures Committee. Their job was to end the conflict.

Rochelle sat at the head of the table. She wore a close-cropped afro and a unitard with a flowing red scarf. Next to her was her second-in-line, Feng. He was thin and gray-haired, with the sinewy muscles of a long-distance runner. At the other end of the table was Alejandro. By some unbelievable stroke of bad luck, he’d been assigned to the same committee as Lily.

Lily snuck a glance at him. She used to spend every meeting watching his every move, but in the last few weeks she’d felt her interest in him fading. In fact, she hardly cared about him at all. Maybe it was a sign she was moving along in the hybridization process. Maybe not. There was no way to know what part of her thoughts and emotions were human and what part Duo anymore. Either way, she was glad to be rid of the dull ache that had taken up residence in her chest after he’d said he wasn’t interested.

“Lily? Are you listening?” said Feng.

Lily blinked. She hadn’t noticed the meeting had started. “Oh, yes,” she said. “I’m sorry, what was the question?”

Rochelle smiled sweetly at Lily. Rochelle always smiled sweetly no matter what anyone said, which meant you could never tell when she was angry. “We were talking about infrastructure.”

Feng leaned forward. “Every time we rebuild, we’re diverting resources that could help the rest of us survive. It’s not a sustainable solution.”

“No one is suggesting we let it continue,” said Rochelle. “What happened with the Manitoba Resolution?”

“I tried to make sure they understood they’d have complete control of the territory, but they were so busy making threats, I don’t think they heard much of what I said,” said Feng.

“There’s got to be a way to get them back to the negotiating table,” said Alejandro.

Lily watched Alejandro’s mouth as he spoke. When she first started going to the committee meetings, she’d spent half her time imagining what it would feel like to run her tongue along the inside of his lip. Now she felt practically nothing.

“We’re going in circles here. In the meanwhile, they’ve got an army amassing thirty miles away,” said Feng. “They don’t want peace. They want to kill every Duo on the planet. They actually told us that. These people are completely devoid of reason.”

A niggling thought entered Lily’s mind. She hadn’t heard from Wes since the day she left the house. She wondered if he’d been involved with rebel bombings. She pushed the idea away, and it slithered into the back of her mind like an earthworm.

“I agree with Feng,” said Lily. “We have to stop playing the pacifists.”

The faces at the table turned toward her.

Talking in front of groups used to mortify her. Every time she had to get up and her face would heat up to a shade of purple. But there was no rash of color in her cheeks now. She wasn’t nervous at all.

“What are you suggesting? We attack the rebels?” Alejandro snorted. “That’s against everything the Enlightenment stands for.”

“How do you know? It’s not like we got a list of instructions. Maybe we’re supposed to be reasonable enough to defend ourselves,” said Lily.

“Self-defense is not the same as an attack,” said Alejandro. His voice had a little whine to it.

Lily ignored him. “The rebels believe we won’t fight back. So, we prepare. Then, when the time is right, we provoke them.”

“‘Prepare’? You mean set a trap?” said Feng.

“It’s not entrapment. The rebels already know we outnumber them,” said Lily. “We put a team together and kidnap their leader. We bring him back here. The rational response would be for the rebels to sacrifice their leader for the greater good, but they won’t respond rationally. They’ll attack, and they’ll die. Once the armed faction is gone, we can move the women, children, and elderly to Manitoba. Pure-blood numbers will dwindle and the situation will resolve itself within a generation.”

Shock hung in the air for a moment.

Rochelle’s glance flicked from face to face, as if she were taking a visual poll.

Alejandro gaped at Lily. “You’re talking about genocide. That’s the definition of unethical.”

Lily turned her eyes to him. “The eradication of the rebel population would benefit the planet and its remaining inhabitants. How is that not an ethical aim?” The words fell from her mouth like stones.

Rochelle smiled sweetly. “I knew there was a reason we chose you.”

VII.

A door rattled behind Lily.

It had taken some time, but the Duo government had eventually been able to kidnap Stone, the rebel leader. The government center hadn’t been built to house a jail of any sort, since they were generally unnecessary these days, but they’d made do with a few bars on the windows and a series of high-powered locks. More difficult had been the acquisition and placement of automated weaponry on the perimeters of the government center. But it had been done. Lily had seen to it.

The door rattled again.

“Hello? I’d like some food in here. Unless you’re planning to starve me.” It was Stone’s voice. Lily had only really met him once, but she already knew she didn’t like him. He had a buzz cut and the body of a boxer. If you looked at him from the neck down, he seemed like an average beef cake. It was just his smirk that gave away his intelligence.

Lily gathered everything she needed on a tray. She had his lunch on one side. On the other, she had a video device. They needed proof that Stone was still alive if they were going to provoke the rebels into attacking the government center to save him.

Lily clicked open the locks and entered the room. It was bare apart from a toilet, a bed, and table. She put the tray down as Stone took a seat. He eyed the video device.

“What’s that for?” he asked.